THE ATOMIC BOMB MISSION

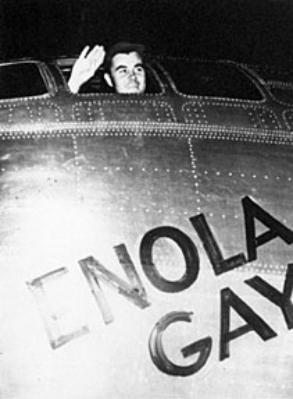

We did not know what was going on. When I say "we", I mean the enlisted men at least. Now, maybe the officers knew, the pilots may have known, the bombardier might have known, I don't know who knew, who did not know; I knew that the enlisted men like myself did not know what was going on. I remember looking out the little scanner's window and yelling to Al, the radar operator who had no window, "You should see what's going on, on Tibett's plane tonight!" It was one thirty in the morning. "It's all lit up like a Christmas tree. They've got spotlights on it, there are news photographers out there, there are cameras out there, and there are a hundred people around that one plane. Where do you suppose he's going tonight?" And Al said, "I don't know." I said, "On top of it, they've even painted a name on its nose!" He never had a name on the nose of his ship. Al said, "What does it say?" I said, "I can't read it - too far away". I later found out, he had painted on there ENOLA GAY. That was the name of his mother.

The plane I was in was called STRAIGHT FLUSH. It was a picture of a Jap going down a toilet. And Uncle Sam's arm was pulling the chain. That was painted on from the time we got to Tinian.

So we took off. And our mission that night - there was no bomb in our front bomb bay; it was empty - was to go on a weather mission, meaning to find out what the weather was like over a certain city in Japan and radio that back to them because somebody behind us was going to come and bomb it. We, the enlisted, didn't even know what city. So we take off and fly six and a half or seven hours, we look down on this city, and it's beautiful. It looks like Chicago. There are beautiful canals and rivers, beautiful sunlight, clouds, beautiful! So we radio back in code, "You can see Hiroshima". That was the primary target for the first atomic bomb. So, my group commander was flying the Enola Gay. He was picked because he was the group commander. And he came in 20 minutes behind us and blew up the city. We did not see his bomb go off; we did not know that he was coming in behind us. All we knew was, we did what we were supposed to do, radio back the weather report to Tinian.

I'm listening to Radio Saipan; it was an armed forces radio network - and I hear, "President Truman has just announced that the first atomic bomb has been dropped on Hiroshima." And so forth and so on, and went on to describe this horrible bomb. And I'm sick in the pit of my stomach, because I'm thinking we blew up our prisoners of war. We had been told they were there. A little while later my pilot crawled back through this tunnel that went across both bomb bays and dropped down beside me and he said, "What do you think?" I said, "I'm sick, skipper. Weren't we told, don't bomb those cities? I just heard on Radio Saipan that they blew up Hiroshima." He said, "That was the cover; there are no prisoners of war stashed there. That was just to have a city that had never before been bombed." Well, then I felt much better. I mean, I wasn't jumping up and down with glee but nevertheless, it didn't make any difference to me, it was just bombing another city.

When we got back we all got two air medals - one for flying the fifth mission and one for flying on the atomic mission. The reason that it was important was not because the air medals meant anything; they didn't - it was because you got points for so many medals. And the points determined how soon you could get out of the service. You got a point for every month that you were in the service, and I was in two years, or twenty-four points - you needed thirty-seven points to get out. And I had two air medals at five points each, that was 10 more, so I had thirty-four points, which meant I only had to stay in the service three more months, which was wonderful.

I didn't stay on Tinian for these three months. Interestingly, you would think that the first that got there would get off the first, and people like ourselves who got there last would get off last. No, el wrongo. It doesn't work that way. They said, "These guys are heroes." - We weren't. But they thought we were useful to the Air Force for publicity purposes. They said, "Put them all on their planes and fly them back immediately." So, we put the whole ground crew on each plane, as well as the air crew, and within two weeks we were all back in California. From California we were given passes home for forty-five days and told after the forty-fifth day to report to Roswell, New Mexico to finish out our time.

Next chapter: After the war