The 509th COMPOSITE GROUP

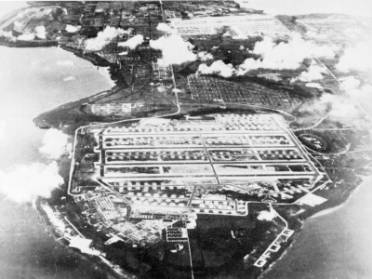

North Field, Tinian

Straight Flush

Tinian

Finally, we went overseas. We took off from Wendover, Utah, to California and stayed overnight somewhere, I don't know where. From there we flew to Hawaii, stayed overnight and then to an atoll called Kwajalein. It was six feet above sea level and was as long as it would take to land a B-29 and was about a half mile wide. There was a sign at the beginning of it. I know 'cause we passed it as we taxied down the runway. It says, "Your are now on Kwajalin atoll. No women atoll, no booze atoll; nothing atoll!" So they said, "You stay here for the night in this Quonset hut." So we go in there and the first thing I notice is that there are some rats running around the ceiling, on these rafters. And I thought, "The heck with that boy, I'm not sleeping with any rats!" I went out, got in the plane, pulled the ladder in behind me, closed all the doors and slept in the plane.

The next stop was to be Tinian. Tinian is an island in the Mariana group of islands in the South Pacific and that was to be our base.

So we land, we pull up to a hangar, we all get out; it's our first time where we were going to be. A sergeant comes up in a jeep and we're all getting out of the plane. In front of the plane, the pilot, the co-pilot, the navigator, the radio operator, the engineer, the bombardier, they're all coming down the ladder. And in the rear of the plane, there's Al, myself, the tail gunner coming down another ladder. We're all out underneath the plane. The pilot says to the man in the jeep, "Where's the 509th, sergeant?" meaning the 509th Composite Group where we were stationed. "Sir, I don't believe I've ever heard of the 509th." "Yeah, the 393rd Bomb Squadron," the pilot says, "the 509th Composite Group." He's thinking now, "I've got a boob sergeant." The sergeant said, "Sir, I really have never heard of the 393rd Bomb Squadron or the 509th Composite Group." And the pilot said, "This is Tinian, isn't it?" "No sir," he says, "Tinian is about a hundred and twenty-seven miles that way." We landed on the wrong island! That was the last time we ever saw that navigator. We went and flew over to Tinian and that was the last day he was ever our navigator. The pilot figured, "If this guy can't even find Tinian, how's he going to take us to Japan, drop a bomb and bring us back to Tinian?" So we never saw that navigator again; we had a new one the next day.

We had picked up these brand new B-29s from the Boeing plant in Omaha, Nebraska. And these were such unusual B-29s; they made them especially for our outfit. And they were so unusual because, first, today it doesn't mean anything unusual at all when we think of today's airplanes, but then, in 1945, it was really something; they could back up. The propellers could be reversed and the props would make the plane back up. They were also pressurized. Now, we think nothing of getting in an airplane today and talking and having a wonderful time and the plane's flying at 36,000 feet; we don't think anything of it. But, when we were flying in the B-24s and the B-17s, the planes that preceded these B-29s and even other B-29s that preceded these B-29s, they were not pressurized and you had to wear oxygen masks over your face when you were above 10,000 feet. So they were very unusual B-29s.

B-29 pressurized cockpit

And one more thing, which really surprised the heck out of us, they took all the guns off the planes. Now I'm a gunner; I'm a gunner without guns. And the reason they took these turrets off the planes - every so often there were these turrets with two fifty-caliber machine guns sticking out of them - was because they said that it will give us a slipstream look and it'll fly faster. The only guns they left on the plane were the two fifty-caliber machine guns and the one twenty-millimeter cannon in the tail, because that was not in the wind; it wasn't going to do anything except shoot at anybody that may be trying to chase us. So they had too many people on the crew. There were eleven and they didn't need that many. If you have no guns, why would you need that many? Well, the pilot liked me. And he said, "I want you and Al Barsumian on the plane and we'll get rid of these other two guys." The other two guys should have stayed, but he wanted us because he liked us. So he told the other two guys to get lost, and Al and I stayed on the crew. Al became the radar operator; he didn't know anything about radar, but they sent him to radar school and he learned a little bit. And they said, "We're going to make you the assistant flight engineer." Me - a flight engineer! As if I ever had seen what was under the hood of a car! I didn't know anything. They said, "We'll send you to flight engineer school and we'll teach you." So they taught me a little bit of this and that, enough to pass the course, and then I was assistant flight engineer/scanner. And they took off all the turrets and they took all the big bubbles on the side of the plane off, so that you could look outside to shoot the guns. They made it all that way and they just left a little porthole to look outside. So, as a scanner I rode in the back of the plane with Al, the radar operator and the tail gunner, who was way in the back. My job was to look outside when we were going to land and tell the pilot over the intercom microphone that the flaps and gear were down and locked. He couldn't see that from where he's riding, way up in front. Even today, a pilot on a 747 can't look back and see whether his wheels are up or down. He's depending on instruments that are on the dashboard which my pilot had, but he also wanted somebody to visually check it. So my job was to look out and say, "The left gear and flap is full down and locked, sir. The right gear and flap is full down and locked, sir." I'd go over and look out the other porthole.

So then, Al Barsumian, the radar operator, said to me one day, "Let's sing it to him." I said, "What will we sing?" So he made up this song and from then on, when we were ready with the flaps and gears, I would wave at Al, who couldn't see out the plane; he had no windows at all, and we would sing,

We had gone on missions to Japan and had dropped single ten thousand pound bombs. That was the size of the atomic bomb. It was about eight feet long, approximately five feet in diameter. We were dropping bombs that were the identical size and weight as the atomic bomb to give us practice. And the only way it could be loaded was that you would drive over a pit that was down in the ground like an oil pit where you could change your oil. The bomb would be down in there; they would lower it on a hydraulic. And then, you'd pull the plane over and open the front bomb bay. And then it would be lifted up hydraulically into the plane and then fastened with big hooks. And the rear bomb bay, there were two bomb bays on a B-29, had two auxiliary gas tanks, one on top of the other, filled with enough gas to get us back. Cause the plane's wings wouldn't hold enough to get you back from Tinian to Japan. Up and down was 13 hours; a long ride. So we would take off around one in the morning and we would get there around seven-thirty or so. And then we would screw around, look for where we were supposed to be dropping the bomb and then turn around and get back. Five times we did that. We would drop just one large bomb and by ourselves. 10,000 pounds of TNT - it'd blow up a whole block. It was the heaviest bomb that existed. But the United States was sending five to seven hundred B-29s each night over Japan, filled with napalm bombs and they were burning out cities one after the other. And then we come along with one bomb. And the idea was, the cities didn't need anymore bombing, this was to end the war. It was to make them say, "Ok, we give up." Because if we hadn't done what we did, there would have had to have been a land assault. We were going to have to go onto their shores and they were going to conserve all of their energy to keep us off their shores. And it was conservatively estimated that we would have five hundred thousand casualties in the first seven days. And they would have as many or more. Now, casualties don't mean death. But a lot of them would be dead.

So, they told us when we went with these ten thousand pound non-atomic bombs, "Take 'em and here's where you go. You go to this city, you go to that city, you go to that city" which was fine. And they said, "We want you to drop them on a city that is clear - where you can see the city. We don't want you dropping it through clouds. We want to have a picture of it going all the way down to see how good your bombardier is." They were still measuring them. So we would blow up things like fertilizer plants, which make bombs. We would blow up all kinds of factories on these five non-atomic runs - I should say four non-atomic runs. But they said, "No matter where you go, if you can't see and you can find an open city, drop it, but do not drop it on these cities." And they named off about five cities, Hiroshima, Kokura, Nagasaki, and a couple of others. They said, "The reason you should never drop your ten thousand pound TNT bomb on those cities is because that's where American prisoners of war are stashed.

The first time we got over Japan, we were given a city - I don't remember which one. And you can't see it - clouds! You'd see it by radar, but that's not what they wanted. So we fly up and down on one side of Japan; all over it at thirty thousand feet, looking for a hole in the clouds with something to drop it on. And we can't find anything. So I say - wise guy: "Skipper, let's drop it on the Emperor's palace." And there's a long pause. He knows he's not supposed to do that. That'd be like bombing the Vatican! You don't drop on the Emperor's palace! And two or three of the other guys that didn't know any better also said, "Yeah! Good idea. What do you think, skipper?" And Buck, who's half nuts anyway, says to the navigator, Felix, "Felix, give me a heading to Tokyo." Now, that's a hundred and five degrees, turn the plane, even though you can't see anything. "I'll head you right into it." He gets over Tokyo and he tells Kenny, "Drop it." Kenny drops the bomb on Tokyo. And Tokyo has already been firebombed night after night - low level. They flew at low level, five, six, seven hundred planes. So we get back and land. Now, Tokyo Rose was an American woman of Asian descent who had been caught in Japan prior to the beginning of the war. When the war broke, she could not leave. And she was put on their broadcast systems to broadcast to all American soldiers and sailors in the South Pacific. And what she would broadcast would be all the love songs of the time, the big bands and so on. She'd say that she is Tokyo Rose, and this is the kind of music you could be listening to if you would go home back to America. And she would also give news. Spies were very prevalent. For example, when our outfit, the 509th Composite Group, landed at Tinian Island, the next day Tokyo Rose said on her broadcast, "The 509th Composite Group, 393rd Bomb Squadron, landed yesterday on Tinian."

Well, my pilot started to tell all of his friends, the other pilots, "My guys sing to me." One of my other jobs was when the plane was the ground. You see when a plane is flying, all the lights that you see in the plane, in the cockpit, in the cabin - that's all generated by the, in our days by the engine propellers, but today, by the jet engines. But when the plane gets on the ground and the engines aren't flying, they don't make any light. There's another engine they turn on. In the B-29 days you had to start the engine - it was a mounted six-cylinder Chevrolet engine. So, we we're coming in for the landing now - we had already sang our little song, "Gears and flaps are down" and as we land, I'm back by this Chevrolet engine, and I start it. Now I come back to the microphone quickly and Al and I would sing...oh, and that was called a putt-putt

"Left gear and flap full down sir, right gear and flap full down siiiiiiiiiiiir."

"The putt-putt's on the line sir, the putt-putt's running fine siiiiiiiiiiiiir."

And he knew, "Ok, the auxiliary engine is on."

They had spies everywhere, feeding information to her. So she said that we did a dastardly deed - and we did - that we shouldn't have done that, that Tokyo was already bombed, and that what were we thinking of, to drop one bomb just to try to scare them; it made big news. And it made the Colonel very mad - very, very angry with Eatherly, my pilot. Again.

That was the first time. Then we went on three more missions, which made four. The fifth mission was the atomic bomb mission.

Next chapter: The atomic bomb mission