My father, Walter Jesse Bivans, was born in Guthrie, Oklahoma and was the black sheep of that family, as he used to say. He was always the one to go out and try and do new things. Most of the family, who stayed in Oklahoma and later moved south to Florida and Atlanta, got involved in the Salvation Army and many of the Bivans', both men and women, ended up as Generals in the Salvation Army.

By the time I was about 10 years old, I went to Hayt grammar school and got into a little play, as children do. Some of them are in harmonica clubs, others are in stamp or camera clubs. So another boy and I joined the drama club. This club would meet once a week after school. We were put into a little play and once we had rehearsed it and were ready, it was put on for the entire student body. The parents were invited. The play was called "Dick Whittington," It was about a poor little urchin English boy and I was Dick Whittington. After the play, the drama teacher, Mrs. Strainburg, said to my parents, "Gee whiz; Jackie seems to has some promise along the lines of acting; maybe you and Mr. Bivans would like to foster that." So that night they said to me, "would you like to learn something about acting?" and I said, "Yes, I would like that very much."

At that time my father had a beauty shop on Grove street in Evanston called "W. J. Bivans Coiffures" with a very substantial clientele; Mrs. Armour of the meat packing company, Mrs. Bud Long of the pickle company, Mrs. Kraft of Kraft Cheese. My mother ran the shop and my father had two other employees. He said to me, "India Parkhill, the dentist's daughter, studied acting in Chicago at a place called 'the Jack and Jill Players,' taking only students between 5 and 16 years old." And Miss Foley, who ran the "Jack and Jill Players," taught these children how to speak, how to be in a play and how to move on a stage. She taught make-up, costuming and everything, and she had teachers who worked for her. It was a pretty good-sized operation located at 820 N. Michigan Ave., which today is DePaul University. This was in 1935 or so and I was about ten. So, my mother called them for an audition to see if I was good enough to join. They liked me and said that they would take me on as a student. Now, frankly, I think they would have taken anybody. It was 25 dollars a month, which was a lot of money in 1935. For example, my mother would give me a nickel and tell me to go to the store and get a loaf of bread. So Miss Foley started to put me along with other children in 10 to 15 years old range and some younger, into plays. We would go to the Civic Theater on Saturdays and put on these plays for other children and she would charge, of course, for people to come and see them. That's where I was first was on stage, in a play called "Cinderella and Her Cat". And I had no lines; I played the cat. I would wear a cat costume and would jump around and hide under her table and she would pet me and tell me what a nice kitty I was. I can't remember the rest of the story, except that the stage was huge compared to many others that I worked on during the years

At that time, there was no television and Miss Foley, who ran and owned the Jack and Jill Players, also supplied to the radio directors and producers the children who would be in soap operas, kid shows and things that were on the radio - dramatic radio programs. After the radio company had told her which kind of young actors they needed, she would send a group of her very best students to audition. But she would not send me, because I was still learning and was not good enough, in her opinion, to even be sent on an audition..

One day, my mother and I were at Miss Foley's late in the afternoon. We were the last two persons there except for Miss Foley and she was telling my mother how she wanted her to make a certain costume for a play I was going to be in called "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves." She was telling her how to make this costume, because the parents had to make all the costumes. The phone rang; Miss Foley answered it and my mother and I are standing there and she said, "Oh, Mr. Wallace, I don't understand that; he knew he was supposed to be there. He should have been there an hour ago.... Well, I am terribly embarrassed, Mr. Wallace; this is just awful. I can't imagine where that boy could be.... Oh, of course, I have another boy right here with me now. I could send him over in a cab and he'd do a fine job for you." Now my mother and I are looking at each other and we know she must be talking about me! And yet, she also knows that I don't know very much; I had been in her school for only six months. She said, "Well, I'll send him right over and don't worry about a thing, Mr. Wallace." So, I was sent with my mother to a place called "World Broadcasting" for a commercial. Miss Foley said to walk in like we owned the place and pretend that we have done that many, many times. She gave me a pencil to mark my parts on the script so they would be easy to see and they'd think I am a real professional. She also said to my mother that when asked for a union card, she was to say that she left it at home and that we would have to get one the next day. We later found out, incidentally, that the kid that didn't show up had gone to the movies; he'd just forgotten about the show.

So I went into the studio and the announcer was there. His name was Franklin McCormack, who later became a good friend of mine and worked on a radio program in Chicago called "WGN All Night Long" for many, many years. So Franklin McCormack was the announcer and I was playing the part of his son. We were supposed to be on the ground out at Old Faithful, that's that geyser that spouts up way up on the air. The first line was mine, and Miss Foley had told me, "Watch the control room. When the director points his finger at you, you start talking, and don't shout, just get excited and talk like people talk." So he points at me and I read my line, "Gee dad, there it goes!" and the soundman makes "wooosssshhhhhhhh!." - the sound of the geyser going up in the air. And the father has to say, "Yes, son, isn't this something? We're here watching Old Faithful and we came out here on Northwestern Railroad!" - or words did that effect. And the director said, "That's fine." We recorded it and he said, "Thank you very much." He never asked if I had a union card, he never asked what my social security number was, but my mother said, "I'll call in Jackie's social security card number tomorrow as soon as I get it from my files at home." - so I could get paid.

After I did that commercial, I thought, "Well, I'm off and running," and the next morning we went and joined the union. It cost me five dollars. This union was the A.F.R.A., American Federation of Radio Artists, which today is called A.F.T.R.A., American Federation of Radio and Television Artists. And I got my social security card and I got paid for that commercial. I don't know how much I got paid, maybe ten dollars or something like that; it wasn't much money. But it was the union scale, whatever it was. And my mother got a phone call from Miss Foley and said that Mr. Wallace liked me very much and wanted to use me on another commercial next week. And she also said, "I want Mr. Bivans and you to come down to my office because now I have to sign a contract with you. You didn't know this, but all of my boys and girls that I put on radio programs and act as their agent - their parents have to sign a contract with me, giving me ten percent of all their earnings, and it's a three-year contract." So they said, "Wonderful!" thinking, "She's going to send Jackie out and he's going to make a lot of money!" Well, I got sent on audition after audition (I was ten years old), but I was going out with professional kids. These kids were like the movie stars, they could tap dance and sing and act like nobody's business. They were Shirley Temples of radio. And I don't think I got any more jobs. I never won another audition for about two years.

But then, luck started to turn my way. By the time I was twelve or thirteen, things started to happen. I would be sent on an audition and occasionally I would snag one; I would win! And maybe it would be for five weeks in a show called Road of Life. I finally ended up on a program called Ma Perkins. It was a soap opera sponsored by Oxydol, and they would send a case of Oxydol to my mother every week as a bonus. And I was Ma Perkins' nephew. Junior was his name in the story and I was in that for several years. I was the only child on that show. The adults were very nice, very pleasant. I grew up in a kind of an adult world because my mother could see that there was a lot of money to be made in this business.

But you had to be in the right place at the right time, so you couldn't wait for Miss Foley to send you on an audition. My mother would take me one day to NBC, for example, which was then on the nineteenth floor of the Merchandise Mart in Chicago. And she said, "We'll just sit here and wait for a director to come through the lobby." And she'd see a director and say, "There is Mr. Magner; Mr. Magner directs." And she told me the name of the show. "Go say hello to him." She would just sit on the bench. And I would run across the row and say, "Mr. Magner, it's so nice to see you! Jack Bivans is my name." "Yes, Jackie, and it's nice to see you." and he'd keep right on walking. I'd say, "Do you have anything coming up Mr. Magner? I sure would like to work for you." "No, I don't have any boys coming into my stories now, Jackie, but I'll keep you in mind." And he'd keep right on walking and then I would go back and sit down by my mother and wait for another pigeon to come walking through there. The next day we would be at CBS or the Blue Network.

Ovaltine originally sponsored "Little Orphan Annie", which was a story about a girl, her dog Sandy and a friend of hers named Daddy Warbucks, who had a diamond in his shirt as a stickpin, so you knew he was very wealthy. And he took care of Little Orphan Annie, which, as we know, later became a movie and a stage play. The first running part I ever had was on Little Orphan Annie when I was in their dramatized commercials on many different occasions. And the commercials always took on the same hue; they were always written in a similar vein. There would be two boys in the story of the commercial, plus the announcer. The two boys were to give a demonstration of one who drank a lot of Ovaltine, so he was always healthier and happier and sounded nicer and huskier. That would be the boy that I would usually play. And then there was another kid in town named Cornelias J. Peoples or Corny Peoples, who an older guy but he was built like a jockey; a real skinny kid and he had a high shrilled thin pitched voice, and he played boy number two.

The commercials would only change by the season. In the summertime you would hear birds - the soundmen would be making birds sounds, and you would hear water gently lapping close by. Mike, the soundman, had a great big tub of water with a microphone hanging over it. Pierre Andre, the announcer, would say, "Here's a scene that you boys and girls will recreate for yourselves this summer."

The people that were in the commercials always came to rehearsal about a half an hour or forty-five minutes after the rest of the cast had been there rehearsing their parts. Little Orphan Annie was one of the shows that I had listened to at home and I was so thrilled to get a call to be on Little Orphan Annie's commercial, just so that I could see her and talk to her or meet her! And so, I got there about forty-five minutes later and the cast had quit rehearsing their part and now they're going to rehearse the commercial. And they did rehearse the commercial, and after the commercial was over, the director pushed the talk back, and he said, "Ok, we're ready to go on the air - the commercial sounds fine." And I'm looking around the studio, 'cause I wasn't introduced to anybody and I don't see the little girl.

Who is Little Orphan Annie? Where is she? And I'm thinking, "There's another little girl who's going to walk in here any second." And, by George, nobody walked in. The show goes on the air and this woman comes up to the microphone and she is Little Orphan Annie. She's got her voice and everything, and she's an old bag! Well, she's probably twenty years, old but to me she was an old bag. And the guy that I figured was Daddy Warbucks, the well-dressed man and the grey hair and nice gray pinstripe suit, he steps over to the microphone and goes, "Woof!" and, my golly, he's Sandy! I can't believe it. Which brings you back to earth. You start the think, "Oh my golly; this is radio; what difference does it make, how anybody looks? Nobody can see us anyway. All they care about is how you sound."

Little Orphan Annie was on from 1930 to about 1940. It was one of the first nice things that I could point to in my career - to say, "I was on Little Orphan Annie" - even though it was only in the commercials.

CHILDHOOD AND EARLY CAREER

Franklin McCormack

My mother, Edna Mae Cooney was from La Crosse, Wisconsin, and my mother and my father met in Chicago where he ended up after World War One. During the war he was with the 13th Engineers and was all over France with troop trains.

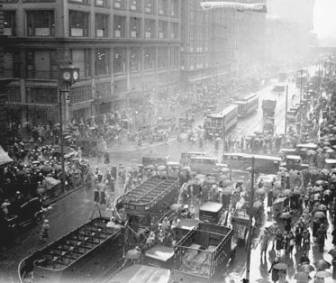

I remember that every year, a few weeks before Christmas, my mother would take me downtown on a bus and we'd go to State Street, "that great street." She would point to Madison and State and tell me that it was the busiest corner in the world. Anyway, we would buy a pair of knickers; we all wore corduroy knickers, and high-topped boots that came up to the bottom of the knickers. And the right boot, on the outside of your leg, had a little pocket with a button flap. And it held a scout knife. When you bought the boot, they gave you the knife.

It was so wonderful; every year getting a new pair of boots, because you'd ruin them with the snow. We had double decked busses and a ride cost a nickel or ten cents. The top was open, so in the winter, you could only use the bottom half. But in the summer, you'd sit outside there, up above. It was wonderful...

A funny story about Chicago

My mother and father and I were taking to dinner one of my dad's brothers, who had come to Chicago for a visit for a day or two. He brought his wife, too. So there is my mother, my father, myself, my uncle and my aunt by marriage, sitting in this restaurant on Wilson Avenue. Now, my uncle, who is a Salvation Army guy, and his wife had just got through talking about the gangsters in Chicago; what they had heard - Al Capone and all these bad people and so on. And my father had just got through telling them that, "That's in the past. Al Capone's no longer here. He's in Alcatraz. We don't have those kinds of things anymore. Chicago is a wonderful town." My dad pays the check and the waitress brings the change and says, "Here's your change, but I wouldn't leave just now, because they're holding up the currency store right next door and the place is surrounded by cops waiting for the robbers to come out!" So we all sat there until the cops arrested these guys coming out of the building they were robbing, right next door to the restaurant. And then we left. Boy, my uncle wouldn't let my dad up after that!

Next chapter: School

The soundman had a big block of wood and he'd splash it in this tub of water and the water would go all over the floor and the soundman would splash another one in there and it was the sound of the two boys diving into the water. The soundman would be churning the water with his arms and the two boys would be close on-mic and you would hear the water churning and the two boys would be panting; they're out of breath. The soundman would make a scrambling sound up onto the raft and then he'd make another scrambling sound up onto the raft, and then boy one would say, "See! Told you so!" And boy two would say, "Oh, you always win." And Pierre Andre, the announcer, would say, "Yes, and you can be a winner too, when you drink Ovaltine." Then he would go into about a thirty second commercial for Ovaltine and those were the dramatized commercials that were in Little Orphan Annie.

Boy one would say, "Beat you at the raft!" Boy two would say, "Oh! No you won't!" Boy one would say, "Ready, set, go!"

One time I asked him what he did on those trains; did he throw coal or wood into the fire - what did he do? He said he cut the Colonel's hair. Perhaps that was his first experience in barbering. When he got out of the service after World War One, why, he got into the beauty business, of all things. My first recollection, when I was 5 or 6, was that he had two beauty shops in Chicago, one on Wilson Ave and the other on Howard Street. We lived on the north side of Chicago.